The following is a guest post by Frank Beard. Beard is a Des Moines, Iowa-based retail analyst, speaker and writer who currently works in marketing and customer experience at Standard AI.

I have a fascination with distressed legacy retailers.

As I’m sure many readers would agree, visiting stores from the once-iconic brands that dominate “retail apocalypse” headlines often feels like stepping into a time machine. It’s as if they’re coasting on the momentum of the past and have confused being present with being relevant. Before my local Toys R Us closed for good in 2018, I discovered that the registers sat upon the same, now-deteriorating countertops where I used to place Nintendo 64 games back in 1996.

I think about this a lot as I visit convenience stores. Despite innovative brands such as Sheetz, Wawa, Casey’s, Kum & Go, Buc-ee’s, and others, I still encounter many stores that join legacy retailers in providing a trip down memory lane. Only they seemed to have gotten a free pass on the disruption that decimated many of our local malls and department stores.

I find the resilience of convenience retail fascinating and attribute it to two factors in particular: a powerful moat around the business through the sale of fuel — an advantage our struggling local malls never had — and extreme proximity to consumers. Ninety-three percent of Americans live within ten minutes of their stores, and even the most basic “smokes and Cokes” offer can still be relevant for impulse and immediacy in a way that is historically difficult for eCommerce.

But this dynamic is beginning to shift. Convenience retailers now face two potentially-disruptive headwinds that, in my opinion, require careful consideration.

Challenges to the traditional playbook

It seems very likely that the ability of the fuel canopy to generate traffic will decline. On one hand, the internal combustion engine is losing its appetite for fuel. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts a 47% improvement in light-duty fleet economy by 2040. On the other hand, the electric vehicles that consumers have begun to embrace don’t even require fuel.

The latter point is particularly interesting. There’s a debate happening right now as to what role convenience retailers will play in providing access to public chargers. Although the idea of adding chargers to a “gas station” sounds forward-thinking on the surface, it’s very easy to be skeptical about the business case.

Convenience retailers currently sell 80% of America’s gasoline, but it’s difficult to see a pathway to charging 80% of America’s electric vehicles. Retailers will have to compete with chargers at home, at work, and at many other businesses that decide to offer them. Additionally, charging seems to be an activity that’s ideally suited for endpoints where the car is parked for extended periods of time. Although a more robust charging network is needed as a safety net, it’s difficult to see why the average EV owner in ten years would need to regularly stop and “fill up” as they travel from Point A to Point B.

Even in Norway, the world’s most developed EV market, some reports suggest that as many as 65% of EV owners living in apartments may be charging at home weekly or more frequently. This new dynamic was also described in Alimentation Couche-Tard’s most recent investor day presentation where it was said that 55-75% of charging activity will occur at home, 20-35% at destinations, and 10-20% while in transit.

How this shift plays out is anyone’s guess. Will diesel demand be resilient? Perhaps. Will the internal combustion engine have a long off-ramp? Potentially. Will there be other energy sources in the mix? Possibly. But when I speak with retailers privately, I hear intense skepticism about the unit economics and potential demand for public charging at their stations.

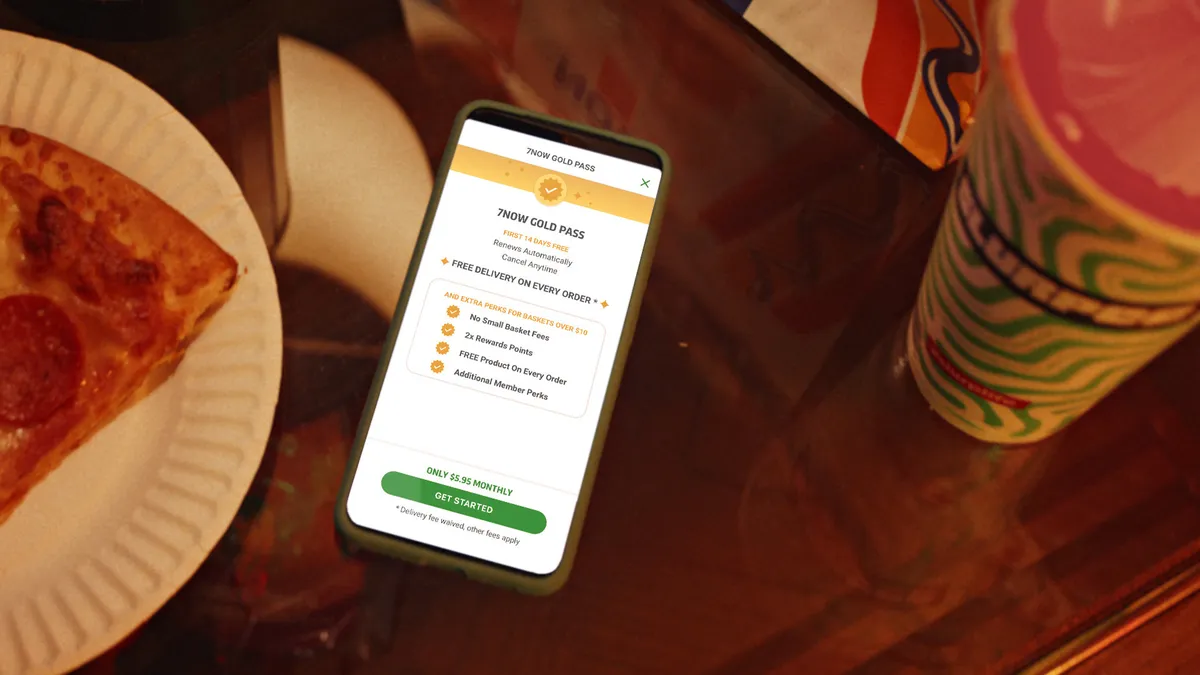

Moving from the fuel canopy to the store, convenience retailers also face an additional challenge as “instant needs” delivery companies compete for the industry’s $255.6 billion in inside sales. The risk here is not outright disruption, but rather being seen as the inconvenient option. What happens when some of the late-night beer runs shift to delivery, or a few busy locals decide that their time is worth more than the cost of Gopuff or DashMart? Retailers need to decide what they stand to lose if access to their store is restricted to a physical point of sale or their own delivery solutions aren’t competitive.

Taken together, these are real structural challenges. An eventual decline in fuel demand risks a shakeout of America's convenience store network in areas where there's a prevalence of home charging. Retailers will have to become destinations for something else, and “smokes and Cokes" is unlikely to be enough. Moreover, continued growth in instant needs delivery options has the potential to chip away at inside sales in a significant way, especially for those who rely on undifferentiated product offers.

As retailers look to utilize their real estate in new and more effective ways, I suspect we'll see a renewed focus on a shift that’s already been happening for the past few decades and is viewed as one of the largest areas for growth in convenience retail.

I’m of course talking about foodservice.

Meet me for lunch at the gas station

Prepared food at convenience stores is nothing new. But whereas the idea of eating at a “gas station” once conjured images of greasy roller dogs, many of today’s leading retailers have offers that rival the national quick-service restaurant brands — and others are fighting to catch up.

It’s important to understand that the industry today is diverging in three directions: consolidators, which scale a more traditional approach to convenience retail while bringing operational sophistication and advantageous fuel supply agreements; food-forward retailers, similar to QSRs, that prioritize quality in both product offer and customer experience while having the room in fuel margins that comes from a successful in-store offer; and merchant-canopies, which park large fuel canopies in front of mega-retailers like Sam’s Club and Costco. Each of these three are positioned to compete against the rest of the industry for larger slices of a shrinking demand in fuel, but the first two also see foodservice as a key aspect of their in-store operations.

The food-forward segment is where you see the bulk of foodservice innovation. Indeed, many of these retailers have built entire brands around it. Typically represented by regional, private companies, these retailers raise and redefine the industry's standards.

Many were early pioneers in foodservice. Sheetz introduced touchscreen ordering back in 1996, and today they provide fully-customizable, made-to-order meals with flexible dayparts. Whereas I struggled last week to order a bacon McMuffin using the touchscreen at my local McDonald’s and had to get help at the register, customers at Sheetz can easily build whatever breakfast sandwich they want, and do so after 10:30am.

In Louisiana, Shop Rite’s Bourbon Street Deli also offers touchscreen ordering and customization, along with an authentic Cajun menu capable of competing with local full-service restaurants. During my last visit, I enjoyed blackened alligator and boudin in a beautifully-themed dining room that had something of a Mardi Gras vibe.

Food-forward brands have been particularly aggressive with their coffee programs in recent years. In Tennessee, Twice Daily created a coffee brand called White Bison and has gone so far as to install pour-over systems and feature single-origin beans. Casey’s recently hired top talent from Starbucks, and many of their more than 2,300 stores now feature bean-to-cup machines. At home, I sometimes walk to my local Kum & Go and bring a laptop since their seating area, which is flooded with natural light, feels much more comfortable than my local Starbucks.

Consolidators are also active in the foodservice game even if they don’t tend to be the first movers. I recently enjoyed a breakfast sandwich from Circle K’s new Fresh Food Fast program, and I have to say it was really quite delicious. EG Group also acquired coffee powerhouse Cumberland Farms in 2019, and 7-Eleven gained access to the Laredo Taco Company with a major acquisition in 2018.

Foodservice opens new doors as retailers seek to move beyond a physical point of sale. It’s telling that none of Wawa’s top-25 delivered items on 3rd party aggregators come from major CPG companies. Rather, the top performers are items from their proprietary foodservice menu. Although it would require a separate article to explore the nuances of delivery, convenience stores are also positioned to serve as the instant needs hubs in communities that don’t have access to the Gopuffs and DashMarts of the world.

Some food-forward retailers and consolidators are also finding success with marketplace formats that have the ability to capture visits that previously went to grocery stores. In my market, I’ve watched some of my own family members replace trips to the grocery store with visits to Kwik Trip as they expand their stores around our metropolitan area. Their high-quality, curated offer provides access to staple grocery items without the need to spend an hour walking around a warehouse and navigating a chaotic parking lot.

I remember speaking on a panel at the National Restaurant Association Show a few years ago where we referenced a survey that found Cumberland Farms’ coffee enjoyed higher perceptions of quality than Dunkin’. One individual in the audience seemed downright incensed that we’d even make that suggestion. After all, how could coffee from a “gas station” be better than something from a well-established brand?

I get it, but don’t be surprised if you wake up tomorrow and discover that the best option for coffee or lunch happens to also have fuel pumps. Who knows, maybe it’ll even have electric chargers, too.