Frank Beard works in marketing at Rovertown and writes The Road Ahead, C-Store Dive’s monthly column. Guest columnist Brandon Lawrence is a longtime oil and gas data scientist and the founder of Fuel Insight, a data consultancy.

The phrase “gas station” has fallen out of favor these days.

The convenience retailing industry now tells a very different story about itself, and for good reason. Wawa is a sandwich shop, Casey’s is a pizza restaurant and Buc-ee’s is basically a retail theme park. To simply refer to these businesses as “gas stations” is to gloss over how they’ve become something more.

And yet, fuel remains the foundation of the U.S. convenience retailing industry. This isn’t Japan. It’s not Europe. Americans don’t walk, we drive. The automobile is an intrinsic part of American culture, and it makes sense that our average convenience store is found 50 feet from a fuel canopy.

Can the convenience business be separated from the fuel business and stand on its own? Possibly. And yet, no legacy brand has achieved this at scale. Fuel remains the largest category within the business and a crucial driver of inside sales. In 2022, according to same-firm data from the NACS State of the Industry report, fuel represented 75.85% of sales and 43.52% of gross profits for the average store. In 2021, those figures were 71.40% and 40.25%, respectively.

This fact informs our thought process about electric vehicles. Lost amidst the noise and hype is the reality that retailers need to stay competitive in fuel as long as possible. Fuel may not be a growth category anymore, but it’s an essential category.

And unfortunately for any unprepared retailers, the competition is becoming much more fierce.

Mainstream narratives miss the mark

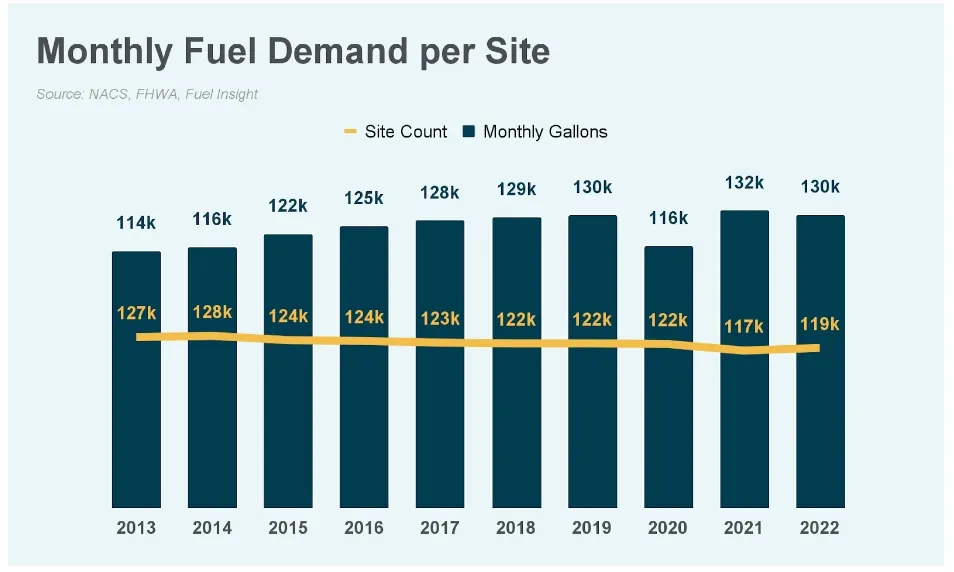

This industry’s cutthroat nature makes it remarkably sensitive to macro demand trends. When demand drops, the industry sheds sites. This results in monthly liquid fuel demand per site being remarkably consistent.

Consider what the industry experienced over the past decade. Site counts slowly decreased in the face of relatively stagnant demand. When COVID-19 arrived, the number of stores dropped dramatically and buoyed the demand available per site.

This is good news for retailers. Although the narratives of the past few years position electrification as something that requires an immediate response, retailers that remain in the fuels game are unlikely to see disruption to monthly site demand, regardless of what happens to macro demand.

Additionally, the mainstream demand destruction narratives have been overblown.

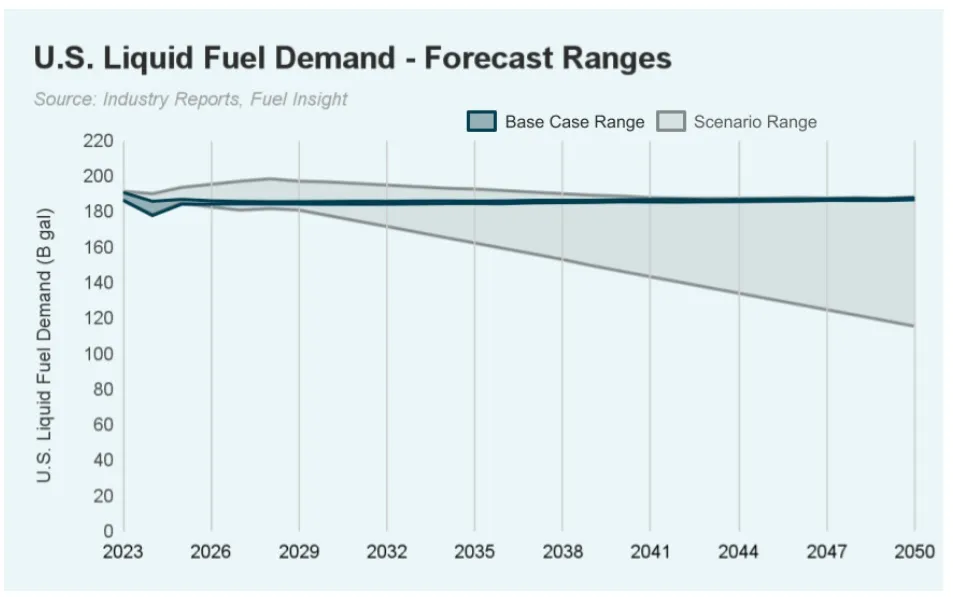

In a review of more than 20 oil demand projections from both inside and outside this industry, we find that the change in demand by 2050 ranges from +1% to -38%. This reinforces a few fundamental realities. Economic output remains a fundamental driver of liquid fuel demand, increased biofuel consumption will likely be required to meet emissions targets and, of course, technology and regulation will remain the biggest wild cards.

But there’s a more cohesive story when we review the base-case scenarios. Worst case, demand is flat from 2022 to 2050. Best case, it may even be up by around 1%. The key trend across forecasts is that electrification and efficiency gains consume incremental growth, but neither is likely to have a material impact on core demand.

This is, of course, a very different story than you hear in the news. If a mainstream publication is tasked with writing about the energy transition, it’s easier to avoid nuance and claim that gas stations are Blockbuster and EVs are Netflix. Similarly, public companies like to show investors that they’re innovative by telling people what they want to hear. At the national level, you might say the tail wags the dog.

But we do see that there’s been recovery in site-level demand post-COVID. By 2021, demand per site had exceeded 2019 levels to set a record high. It’s down slightly in 2022, but more sites have come online while macro demand stayed flat year-over-year.

The events of 2020 were also interesting, because we found the fuel demand floor. For one week in April 2020, barrels per day were down 43.7% year-over-year. This means nearly 60% of liquid fuel demand was absolutely essential to the U.S. economy. Its quick recovery also implies that much greater demand may actually be required to keep the system running.

All of this is to say that we’ve been sold narratives that don’t match reality. Additionally, we see reason to be skeptical about how retailers are being told to react to the presence of electric vehicles.

Disruption or distraction?

The quiet part nobody’s saying out loud is that EV charging is an amenity, not a core value proposition like liquid fuels.

Charging may be a fine amenity at some locations, and it might make little sense at others. It can be helpful to think of this in terms of total addressable miles (TAM). Gasoline is a product where every mile driven is part of a journey that leads right back to another fuel canopy. Each transaction is the beginning of another. The reason why retailers cared so much about traffic count was because the miles those vehicles drove were all addressable.

That’s no longer the case with electric vehicles, and that’s precisely why the push to add EV charging feels so weird. A person who charges once at a convenience store might never have to visit you again. Some EV drivers could go the entire life of their vehicle without using chargers installed by convenience stores.

Convenience retailers sell 80% of America’s gasoline, but there is no pathway to powering 80% of America’s charging demand. Consumers can charge at home, at work, and at other businesses where dwell time already exists. There is no moat around the charging business as there is with liquid fuels.

The reality is that nobody knows what this means. Consider the winning entry in this 2022 design competition for electric charging station concepts: “The modular design allows the station to adapt flexibly to different sites: a rural location may have a cafe and washrooms, while a commuter hub could become a larger facility with everything from an arcade to shops.”

In other words, they designed a strip mall.

That’s why if anyone says they know what this means, they’re likely selling you something. There’s a veritable gold rush to get this technology onto the market, and folks are preying on the uncertainty this industry feels about the energy transition. And to be clear: It is intimidating that there are now vehicles on the road that don’t require gasoline.

But as with any gold rush, the person selling the pick doesn’t necessarily care if you find gold. They just need to sell the pick. And much of the advice being given about how to prepare for this transition is coming from the companies selling the proverbial picks.

It’s okay to take a step back and ask: Is this truly disruption, or will demand follow a consistent glide slope? After all, this supposedly no-brainer revolution has failed to materialize as quickly as folks said it would — even amidst low interest rates.

Retailers shouldn’t ignore what’s happening, but neither should they feel pressured to take immediate action. They have time to figure out what the energy transition means and understand how it impacts their businesses.

Besides, getting too distracted right now runs the risk of missing a much larger issue.

The coming battle in retail fuels

Retailers face an increasingly competitive environment in liquid fuels — one that will become even more fierce.

The big players aren’t going to take their foot off the gas. Casey’s, Circle K, 7-Eleven and other consolidators are gobbling up an increasingly large share of total industry sites. From 2014 to 2022, according to NACS State of the Industry Data, the percentage of total industry sites belonging to chains with 501 or more stores increased from 17% to 22.5% of all convenience stores with a fuel offer. Indeed, the 2022 increase in single-site operators is likely the result of divestments by consolidators rather than new-to-industry growth.

Go-to-market strategies for gasoline and diesel were born out of an environment that, at a certain level, may have been very close to a positive-sum game for some companies. With fuel demand piggybacking on growth in vehicle miles traveled due to population and economic growth, there were environments where nearly everyone could grow gallons without someone else suffering a loss.

Regardless of whether macro fuel demand stagnates or declines, retailers now face a zero-sum game where growing gallons means eating a competitor’s lunch. The big consolidators will attempt to stay in the game as long as possible — and be the last one to close the door and turn off the lights.

That’s why we think the question for 2024 isn’t how retailers might enrich the time of an EV driver, but rather how they’re preparing to remain competitive in retail fuels. Those who find that answer now, while others are distracted elsewhere, will set themselves up for long-term success.

The reality is that liquid fuels will remain the lifeblood of the American economy for many years — perhaps even decades.

This is the time to chart one’s course. Use it wisely.